Could This Ancient Design Technique Help Keep Homes Cooler Without A.C.?

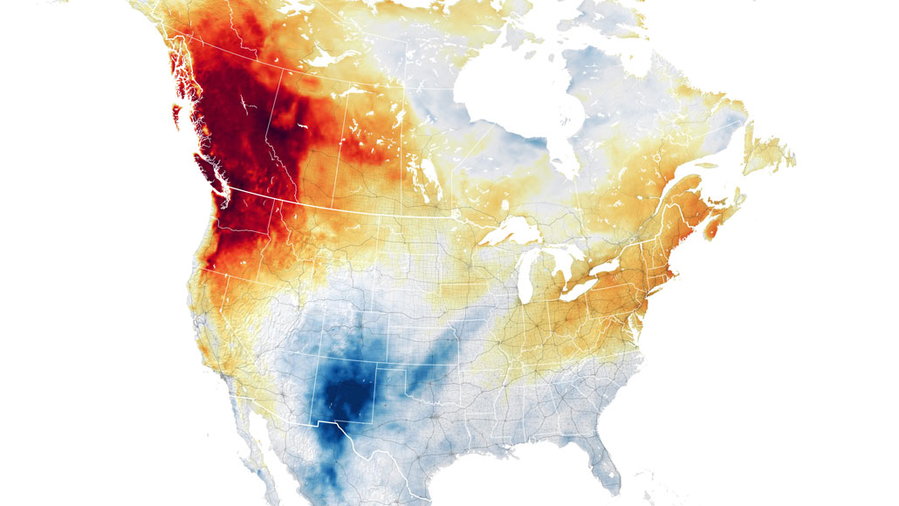

Summer temperatures are heating up, most notably in parts of the country that are unaccustomed to such drastic heat waves like the Pacific Northwest.

Last month, temperatures climbed to as high as 115 degrees in typically cloudy places like Seattle, wreaking havoc in the region. Sudden deaths, wildfires, infrastructure damage, and heat-related emergencies were just some of the side effects of this uncharacteristic and dangerous heat wave. Sadly, temps like these will most likely become the norm as climate change continues to cause extreme weather patterns, such as the ridge that centered itself over the region in June.

But how can areas like the Pacific Northwest rethink their infrastructure to better prepare for such devastating weather patterns?

The answer is a new approach to architecture that departs from the standard, combined with a few more familiar design concepts previously used in the region.

Currently, most homes in the region are designed for much cooler weather, with appropriate ventilation and insulation meant to regulate temperatures and cool them more effectively, rendering standard air conditioning mostly unnecessary. However, in light of last month’s record-breaking temperatures, architects in the Pacific Northwest are focusing on ways to depart from the region’s previously successful strategy of little or no-effort temperature control.

Mike Fowler, a Seattle-based architect at the firm Mithun, is just one of many architects who’s looking toward new ways for architecture to evolve – and design approaches historically used in more extreme climates may provide the answer.

These strategies are already being employed in other areas around the world, as architects are forced to rethink design concepts in response to ever-increasing temperatures. Some of these methods, including using new construction materials; employing advanced heat modeling techniques; and incorporating other, more traditional (and even ancient) architectural and design principles, are proving effective in keeping homes cooler, all without the need for air conditioning. That means less energy consumption and a more sustainable way of living and keeping cool.

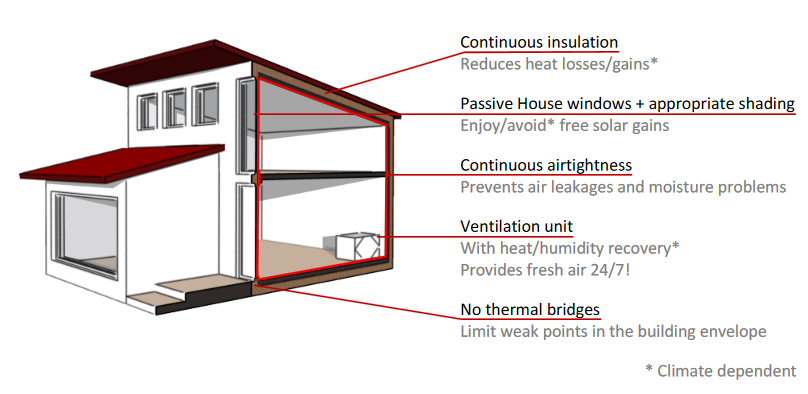

Another such approach that’s proven successful is the building standard known as Passive House. With (official) origins in 1990s Germany, the Passive House concept has since been modified to accommodate varying climates in countries across the globe. The standard essentially turns homes into sealed energy efficient “envelopes” with extremely high insulation, making them more impervious to the temperatures outdoors. To accomplish this, homes are built with windows that are triple-paned, contain heat pumps that are extremely energy efficient, and have highly insulated wall systems. This idea of “passive building” is nothing new – it’s been used for centuries in hotter climates all over the world. However, with temperatures rising in places like the Pacific Northwest, architects are turning to these concepts for new ways to stay cool while also becoming more energy efficient.

Fowler, for one, is on board with Passive House standards, and works with groups like Passive House Northwest to encourage architects and builders to employ these principles. He says that “the pitch [involves] one chance to invest in your building envelope — the windows, roof, and walls. Do it right so that something you build now is going to be resilient into the future.”

Even without meeting “the official standard,” Passive House design concepts are influencing other architects around the world, including the firm Studio Ma in Phoenix, which focuses on designing elements right into their buildings to keep them passively cool. The use of shading, overhangs, and cantilevers also keeps buildings cool in the desert heat. Combined with lighter materials on the outside of the building that have better insulation (versus heavier stone and masonry), the houses’ temperatures can be managed much more effectively.

Christopher Alt, a co-founder of Studio Ma, says that “some people call it ‘outsulation’ because the insulation is on the outside, but it’s very dependent on the climate you’re in.” He feels that though the solution is different in Arizona, the same kind of thinking applies in regions like the Pacific Northwest. Though the two areas have very different climates, the Passive House standard can still be modified and adapted accordingly to incorporate architecture that addresses any region’s specific cooling needs.

Other architects have found that incorporating passive cooling methods into design concepts from the ground up can be both more affordable and energy-efficient. Marlene Imirzian, who runs an architectural firm with offices in California and Arizona, has been using passive cooling elements in many of her projects, and has found that these practices can significantly cut energy consumption – and costs. “It’s not about highly specialized systems. It’s about using natural flows…and designing [spaces] to allow for air movement,” she says.

In many cases, this means implementing practices from the ground up, and building with the goal of reducing energy use while keeping cooler, as part of the initial design strategy. Imirzian’s firm, who had the winning entry in Phoenix’s zero net energy home competition, proved just that, incorporating passive cooling concepts into a 2,100-square-foot home that would cost about the same as an air conditioned home, but requires way less energy to cool. “If we start doing these single family homes well,” Imirzian says, “we can significantly reduce energy use.”

With temperatures on the rise and predictions that, because of climate change, we can expect more extremes in the coming years, architects and designers are rethinking long-held ideas about how homes are built – by looking to the past. With an eye toward less energy consumption via cooling methods that don’t involve air conditioning, these innovative processes could have long-term implications that extend beyond extremely hot climates. As Imirzian says, “[They could be] very, very transferable around the world.” And that’s great news for our warming planet, which needs sustainable solutions now more than ever.