Chicago Gets Its First Renovated Passive House

Woman-owned architecture firm HPZS has completed the first certified single-family Passive House renovation in Chicago, demonstrating that retrofitting America’s older homes to meet energy-efficient goals is possible and can even be done at a profit.

Though climate change objectives are getting more serious government attention these days, innovative ideas are still needed to help reach carbon-emission reducing targets within the next 10 to 30 years. HPZS took on the challenge by transforming a client’s 1890’s Ravenswood neighborhood property into an energy-neutral build for the future.

Called the Yannell PHUIS+ House, the renovation meets all the strict requirements for the Passive House Institute US (PHIUS 2018+) certifications. In contrast to many of the energy upgrades being included in construction today, the passive home concept is all about building materials into the design that save energy without any extra effort. This means that most of the changes are made within walls and structures rather than with more visible systems like solar, smart thermostats, and Powerwalls.

For the Yannell PHUIS+ House, HPZS gutted the century-old residence down to its studs and sheathing boards. Some may wonder if simply demolishing and building fresh would have been a better idea (especially considering the project’s cool $1.4 million price tag), but in many areas, and especially with historic domiciles, there are less fees and red tape involved for renovation applications than for new structures. Plus, it preserves at least some of the original material.

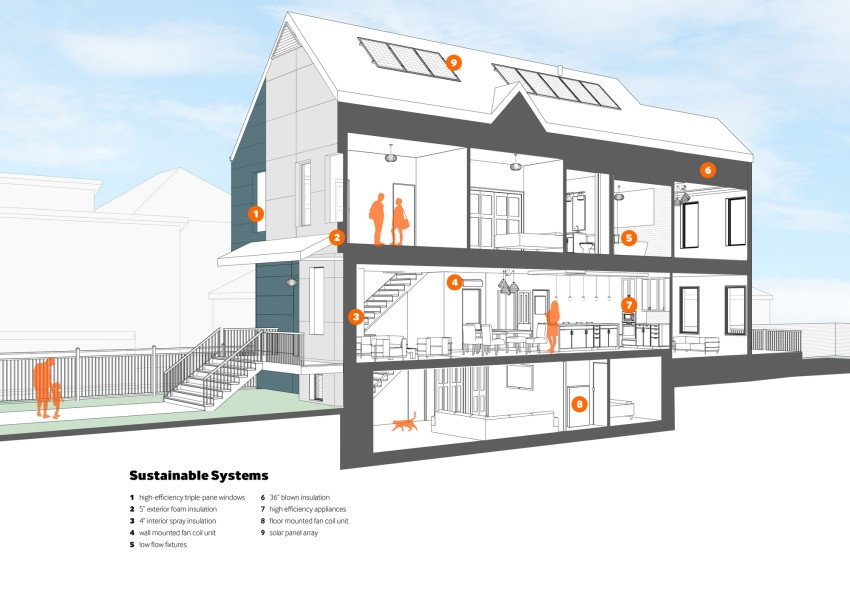

The HPZS team added 500 square feet to the two-story-plus-basement abode, for a finished product of 3,884 square feet, five bedrooms, and three bathrooms. They started by super-insulating the walls with R-48 graphite-infused expanded polystyrene exterior insulation, which adds internal reflectivity and reduces radiant transmission. The internal walls were similarly foamed in with closed-cell polyurethane insulation, while the roof got 36 inches of R-100 blown-in glass mineral wool.

Additionally, HPZS used triple-pane argon-filled insulated windows, saving even more energy and providing abundant natural light inside. To provide clean, fresh air regularly, the firm installed an Energy Recovery Ventilator that harvests heat energy from the outgoing air to heat the incoming oxygen.

While solar power is not an essential part of passive construction, this home does include a 2.8 KW photovoltaic roof-mounted system that produces 25 percent of the house’s annual energy demand.

All of these design decisions resulted in an extremely air-tight edifice with a test score of 0.0596 cubic feet per minute per 50 square feet (an older home built using traditional construction techniques can test up to 120 cf/m). That ultra-low score earned the house three bonus certifications: Zero Energy Ready Home (ZERH) status from the Department of Energy, EPA Energy Star, and an EPA Indoor airPlus label.

The renovated passive house is currently slated to be resold on the speculative housing market for profit.

“For our team, this project was successful because of our tenacity in the face of a difficult design and building science problem: how can you transform existing buildings today to meet 2050 goals,” explain the Chicago-based designers. “But it also represents, to a greater extent, significant policy issues that we’re going to have to deal with if we want to decarbonize: zoning codes must change to allow for exterior insulation to be added within setbacks, major renovations and new construction should not be allowed new natural gas connections, homes should be blower door tested successfully in order to achieve occupancy permits. This project demonstrates that change is essential to the policy administration of the built environment. It’s just one more call to action.”