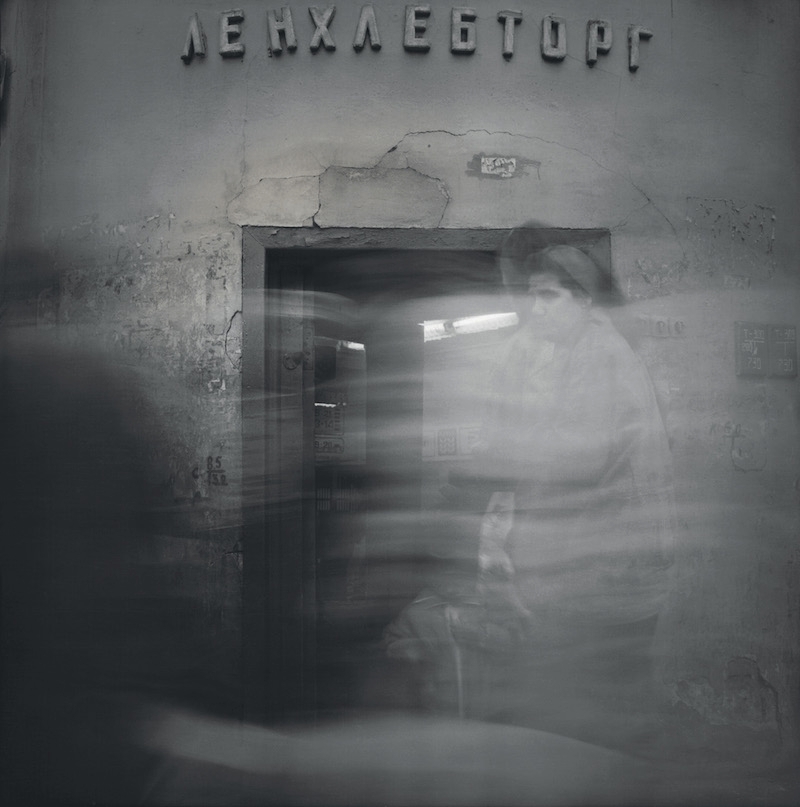

Time-Lapse Ghost Cities by Alexey Titarenko

The rush of the crowd bustling down the street seems a series of particles to those standing and watching in real time. Strip away color and let time lapse, though, and the effect is downright spooky – haunted urban centers, crisp in backdrop but populated with ominous ghouls.

The work of Alexey Titarenko displaces persons, or, conversely, calls attention to their fleeting presence in built environments. His spooky Time Standing Still long exposure photo series from the late 1990s is in large part what drew broader public attention to this increasingly famous photographer, followed by Cities of Shadow and other explorations of humanity in the context of urbanism.

Beyond the jarring first-impression effect of his first forays into non-standard photography, however, his techniques (and subjects) have evolved with time. Subsequent shoots have toyed with more timeless questions of composition, light and shadow in increasingly complex ways.

Titarenko graduated with a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Department of Cinematic and Photographic Art from Leningrad’s Institute of Culture in early 1980s, but it would not be before the end of the decade that he could (as a Russian citizen) declare himself an artist and divorce his work from the state propaganda machines. Subsequently, however, his pieces have been hung at dozens of museums and shown at countless exhibitions around the world.

“I vividly remember the first image, taken at the entrance to the Vasileostrovskaya metro station, located in an old neighborhood, surrounded by factories and shipyards. For the daily commute, the metro was the only public transport in service during this period of crisis. The train is deep underground—more than a two hundred feet—because the soil is so unstable, and access to the platforms is by way of a seemingly interminable escalator. When the escalator broke down, as often happened, entry to the station was restricted to avoid a dangerous crush. At rush hour a crowd of several thousand people would accumulate outside and in waves this human tide climbed up the stairs leading to the entrance of the impressive building on high ground, as was generally the case for most metro stations in Leningrad. Barricaded behind its glass doors, a few policemen were trying desperately to contain the masses of people. In vain, because the crowds were determined to enter at all costs, even if it meant losing a button or a shoe. People pushed, yelled, threw punches. Handicapped people were trampled. It was like a scene from hell. “

“As I watched, shocked and appalled, a musical air emerged in my head, a fragment of Shostakovich that brought me to tears. Not thinking consciously about what I would do, I set up a camera in front of the crowd. No one paid any attention. The exposure time exceeded several minutes and I pretended to wait, to read something in my notebook. Then someone jostled me and I closed the shutter. In the evening, looking at the negative, I experienced the same emotional shock I had felt when the Shostakovich melody came into my mind: deeply moved, almost in tears, but also filled with enthusiasm and excitement. Depicting the crowd as a general movement with erased secondary movements, the metaphor created by the long-exposure effect, made evident certain fixed elements that would otherwise have been drowned in an abundance of details and faces. Yet these were exactly the elements—hands on the stairway rail, for example—that moved me, provoking in me an intense emotional pain I felt at the time as well as a wave of love toward the crowd.”

“The mass of indistinct faces symbolized a precise moment that I had witnessed, but there was more to it. Similar episodes came to mind: wars and revolutions the Russians had suffered throughout their history. It was as if one photograph had embraced a decade, even a century. I felt that my childhood dream of capturing on film a state of the soul or a singular impression experienced in the street had come true—reality as I had felt and imagined it had been recreated. It was this notion of time—as if introduced in a slightly “mechanical” way while keeping the shutter open as long as possible—that transformed what would otherwise be just a simple “document” about a particular era into an actual visionary oeuvre.”