Is It Architectural Borrowing or Plagiarism?

Architects can be inspired by art, fashion, history, and many other aspects of society. Sometimes that inspiration comes from the work of other architects, in which case certain styles or ideas may be borrowed. For example, they might take the concept of an agora and use it to create the masterplan for a new retail project, or they could use a school marquee as inspiration for the marquee of a fitness center. Like an orator borrowing a line from the words of a famous world leader or author in order to make a point, architectural borrowing helps us understand the language of architecture. It can be thrilling to see how one project or style influences others. Of course, there are also times when architectural borrowing verges on plagiarism.

Remember when it was reported that a developer in Chongqing, China copied a building designed by the late Zaha Hadid? We heard about that because it involved one of the most famous architects in the world, but if a lesser-known architect plagiarized the work of another lesser-known architect, would we ever know? Most of us wouldn’t even notice the resemblance, unless we were aware of the work of all the thousands of architects in the world.

Every work of architecture is never 100 percent original. To save time, an architect might take a few elements from one of their past projects and use them for an upcoming one with a similar purpose. This happens frequently in many firms. If something worked in an old project and the client liked it, why reinvent the wheel for the next project? This is when a firm copies elements from themselves — but what about when firms copy other firms?

The Architectural Works Copyright Protection Act (AWCPA), first passed by Congress in 1990, gives copyright to original works of architecture. This protects both the finished product of a building and any architectural drawings that may have been made during the designing process. Even a project that’s deemed to be “substantially similar” to another, whether intentional or not, may be in violation of the AWCPA, so long as the original work is registered with the U.S. Copyright Office within three months of the new one’s publication or before the plagiarist begins the copying.

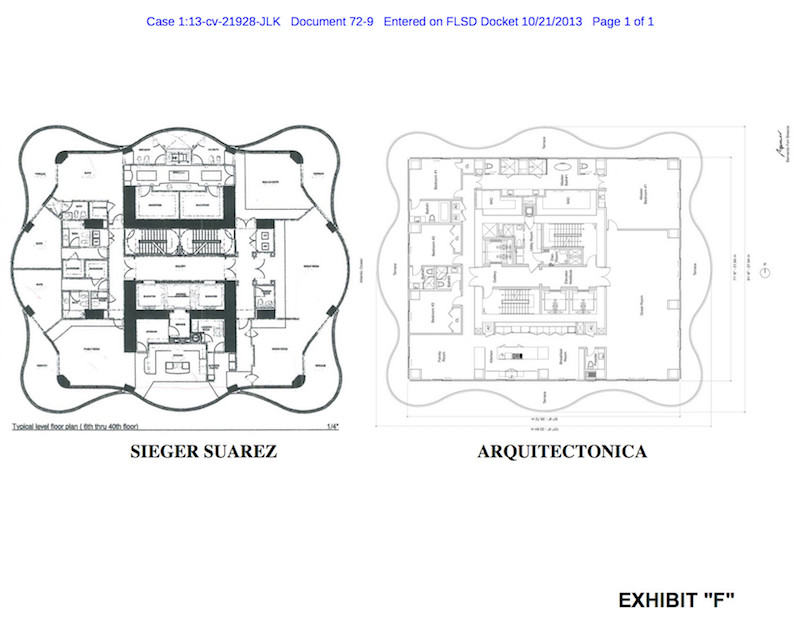

Issues relating to copying tend to arise when a client fires one architect and then hires another one for the same job. In these instances, the work of the first architect is sometimes given to the second without permission. A similar thing happened between Sieger Suarez and Arquitectonica in the 2000s, when the former’s design for a proposed condo tower from 2000 was allegedly used by the latter in 2006 when they took over the project. In February 2014, however, a federal judge ruled that “the usual analysis of substantial similarity [wa]s too vague and the language misleading” with respect to infringement of architectural works in that case.

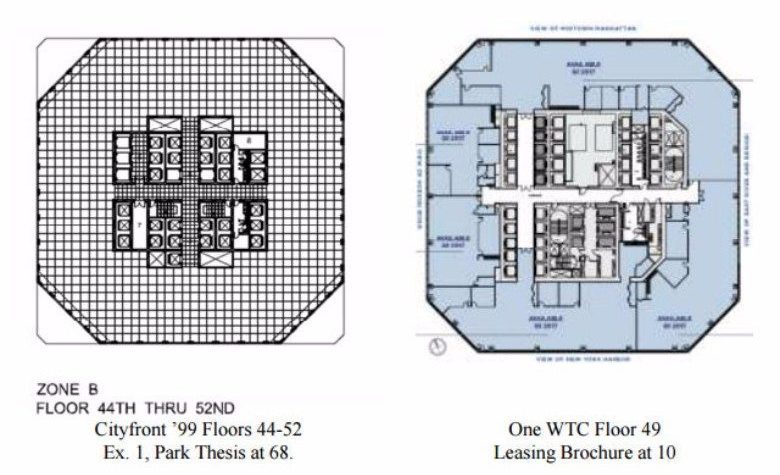

In June 2017, Jeehoon Park (a Georgia-based architect) filed a lawsuit against Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), accusing the firm of stealing the design for One World Trade Center in New York from a project he designed in 1999 as a grad student at the Illinois Institute of Technology. More specifically, Park claimed that One World Trade Center bore a “striking similarity” to one of his works.

Architects will always use the past as inspiration for the present and future. Architectural borrowing turns into architectural plagiarism when projects look strikingly or substantially similar to each other — but even that distinction seems to be pretty vague.