Is Design Thinking Really That Important?

“Design Thinking” (DT) is a term used to encompass the strategies supposedly employed by designers to solve problems and their application in all types of business and social issues, from health to income inequality. Several years ago, it was thought that the DT fad was coming to an end, but in 2018, it’s still flourishing, spreading, and evolving. There are now even university programs in DT funded by banks.

In June 2017, Natasha Jen, a partner at the independent design consultancy Pentagram, gave a provocative speech against DT, in which she explained that some of the solutions that businesses and institutions have attributed to it could also have been achieved without it. Jen also made the point that many of the buzzwords associated with DT, like “servicescape,” “seducible moments,” “affinity diagrams,” and “ideographs,” are rarely used to critique the work of other designers.

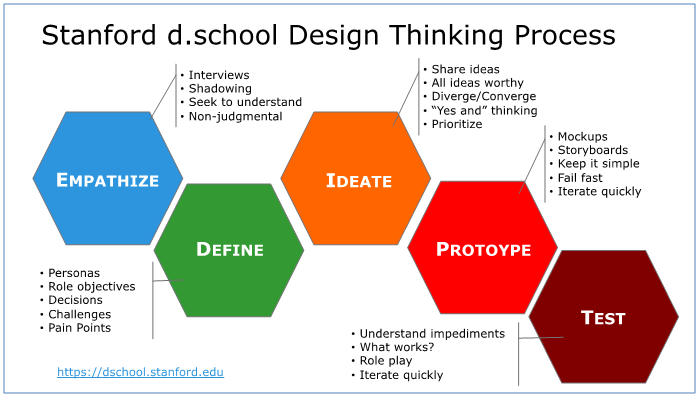

According to Jen, the process of Design Thinking (as thought of and promoted by places like Stanford d.school) is missing a crucial ingredient: criticism. Designers critique their work — and the work of their peers — using concrete terms meant to improve the quality of that work. For example, an architect might critique her own work and find that “symmetry,” an ordering principle, is lacking. An interior designer might critique a colleague’s work as “kitsch.” Words like those have real meaning to designers, unlike many of the terms used in DT.

Is Design Thinking really about design and problem solving, or is it just a commodity for universities and consultants to sell? Will we ever end poverty, racism, and sexism, turn every elementary school student into a genius and every company into an innovation hub through Design Thinking? No, we will not. Proponents of DT may argue that it was never meant to do any of those. To be fair, they may have a point.

New ways of thinking and looking at problems are always welcome, particularly in companies and industries that have complex problems to solve in the first place. Even when it comes to social issues, it can be beneficial to examine how people end up in poverty from a more holistic point of view — one that considers macroeconomic factors. Since designers have a way of thinking through complex problems with success, it’s understandable that other industries or activists fighting social inequality would want to borrow certain aspects of what they do and apply them elsewhere. The problem is, as Natasha Jen mocked, designers do not actually use those words.

Of course, Jen is not mocking genuine attempts to use design for positive change. That is a good thing, and we should see more of it. The real issue is the fact that Design Thinking is a heavily marketed, corporately funded, reductive, and repackaged style of learning, just like “greenwashing” is to environmentalism and “pinkwashing” is to feminism. Design Thinking has unfortunately become a vapid collection of buzzwords, sold for hundreds and thousands of dollars to everyone as a kind of cure-all. We were all intrigued by it at the beginning and embraced its ability to help individuals and companies solve complex problems, but now it’s fair to ask: is design thinking really that important?