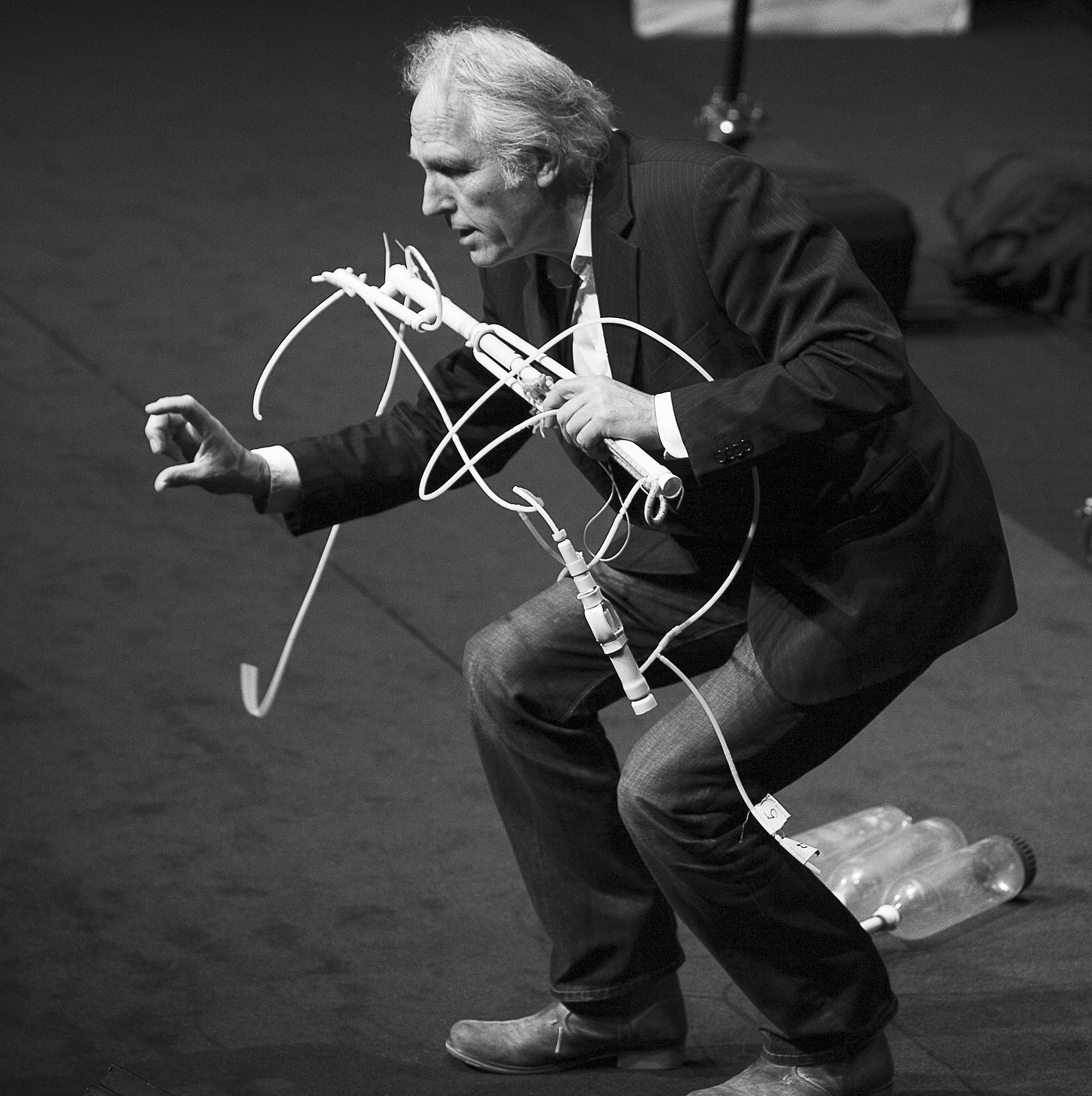

Theo Jansen’s Fabulous ‘Strandbeests’ Roam Along the Beach

Dutch environmental artist Theo Jansen is a real-life genius in the likeness of literary legend Dr. Frankenstein. He brings fabulous creations, or “Strandbeests,” to life so they can wander about on the beach:

“Since 1990 I have been occupied creating new forms of life. Not pollen or seeds but plastic yellow tubes are used as the basis of this new nature. I make skeletons that are able to walk on the wind so they don’t have to eat,” said Theo Jansen.

Strandbeest is Dutch for “beach animal.” You may be more accustomed to the sideways scuttling of crabs or the squabbling of seagulls on a beach near you, but think bigger. Much bigger. Then imagine mega-skeletons with white sails for wings, giant hammers for heads and tubes connected with multiple other tubes for bones and many legs, that walk along together with a pleasing, rippling motion.

Jansen was inspired to draw attention to the erosion of the sand dunes around his native Netherlands and in 1990 he built his first Strandbeest. For the last quarter century, he has improved the construction and engineering of his “skeletons,” in a process of evolution that has enabled him to produce a spectacle of beauty that results from a fabulous synthesis of Strandbeest, wind and wave:

“Over time these skeletons have become increasingly better at surviving the elements such as storm and water and eventually I want to put these animals out in herds on the beaches so they can live their own lives,” Jansen said.

Plastic bottles and tubes collect then direct compressed air around the skeletal structure of each wondrous sand beast, creating compulsive movement. The wind thus drives the motion of legs, sails, heads and also produces lovely sounds—the whooshing of cantilevered wings, the crackling of bones and the sweet clickety-clacking of many knobbly knees.

The tricky technical bit is much better explained by the artist himself, who has given a Latinate name to each sub-species of his Strandbeests:

“Self-propelling beach animals like Animaris Percipiere have a stomach. This consists of recycled plastic bottles containing air that can be pumped up to a high pressure by the wind. This is done using a variety of bicycle pump, needless to say of plastic tubing. Several of these little pumps are driven by wings up at the front of the animal that flap in the breeze. It takes a few hours, but then the bottles are full. They contain a supply of potential wind. Take off the cap and the wind will emerge from the bottle at high speed. The trick is to get that untamed wind under control and use it to move the animal,” Jansen said.

Anthropomorphism is taken to sheer perfection as each Strandbeest is buoyed along the beach. From recycled bottles to engineered fine tubing to what look like massive cardboard boxes, the component parts of each construction do not prepare you for the sheer, magnetic beauty and charm of these seemingly living animals:

“Beach animals have pushing muscles which get longer when told to do so. These consist of a tube containing another that is able to move in and out. There is a rubber ring on the end of the inner tube so that this acts as a piston. When the air runs from the bottles through a small pipe in the tube it pushes the piston outwards and the muscle lengthens. The beach animal’s muscle can best be likened to a bone that gets longer. Muscles can open taps to activate other muscles that open other taps, and so on. This creates control centers that can be compared to brains,” said Jansen.

Man and “Beest”

Fifteen hundred legs with rods of random length were computer-generated to establish the ideal walking curve for Jansen’s Strandbeests and these were whittled down to 100. According to Jansen, “These were awarded the privilege of evolution.”

The computer was left on for months, both day and night – and eventually it produced the 11 “Holy Numbers” that denoted the ideal lengths of the required rods to create the leg of Animaris Currens Vulgaris—the first beach animal to actually walk.

These are artist’s holy numbers: a = 38, b = 41.5, c = 39.3, d = 40.1, e = 55.8, f = 39.4, g = 36.7, h = 65.7, i = 49, j = 50, k = 61.9, l=7.8, m=15. Jensen tells us it is thanks to these numbers that the animals walk the way they do—in a uniform, elegant and non-jerky way.

The very picture of the mad (and brilliant) professor, Jensen creates in his LABATORY YPENBURG, which is a sandpit measuring 30×15 meters, a cabin, a large sea container and many willow trees:

“There is the bone yard as well. Usually there are only one or two animals living at one time. As soon as the development of an animal is at its end, I declare it extinct and I push it onto the bone yard. The animals there can be seen as the fossils of extinct species. Exposure to sun and rain causes the tubes to fade, making these appear more bone-like with time. The sandpit is the pre-heaven for the beach animals. They are not yet ready to survive the real beach. I still have to train them. Usually I take them out once a year to the real beach to let them get a taste of their natural environment,” Jansen said.