How Three Architects Use Old Materials to Make New Architecture

Though new technologies have expanded architecture’s possibilities, the things we expect from structures have not changed: the ideal construction is still basically a roof supported by posts or walls. Material is one of the themes through which the Chicago Architecture Biennial is highlighting history and the ways it can be used as a reference point to come up with new ways of producing architecture. Old materials, sometimes seen as primitive by contemporary architects, can still be used to create new forms of architecture. This can be observed in the work of three architects who were invited to participate in this year’s biennial.

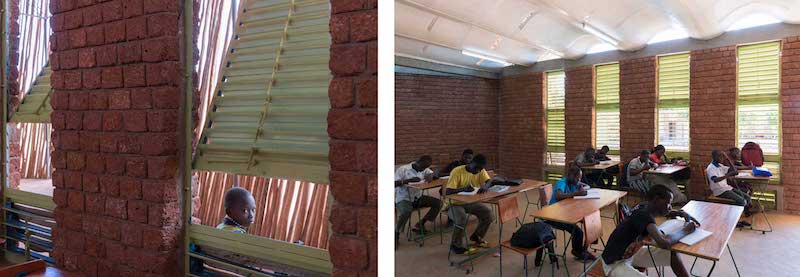

The Lycée Schorge Secondary School in Koudougou, Burkina Faso, by Kéré Architecture marries vernacular materials with modernity and elegant, local style. In plan, the 17,868-square-foot school (built in 2016) is a radial organization of nine solids around a central courtyard. A screen of vertical wooden limbs forms the rhythmic exterior of each volume, the majority of which are used as classrooms, giving the school a well-ventilated and transparent façade. The walls facing the courtyard were built with bricks hewn and formed from laterite stone. Once laterite is brought to the surface, it hardens, providing the walls with extra strength. The classrooms each have an off-white, curvilinear ceiling made of concrete and plaster, which maximize ventilation and enhance natural illumination. Above the ceiling, wind towers help funnel air into the classrooms, while overhanging roofs provide shade for the courtyard’s interior walls.

Studio Mumbai’s design for Melbourne’s MPavilion 2016 is a structure that accentuates the essentials of architecture. “I want it to be a symbol of the elemental nature of communal structures,” explains chief architect Bijoy Jain on the firm’s website. The pavilion’s foundation was built using 100,000 pounds of stone and supports a structure that incorporates 4.3 miles of Indian bamboo, 5,000 wooden pins, and 16 miles of rope in the space of 76 square feet. The inclined sides of the roof took craftspeople four months to weave together. Under the structure, and at the center of the project, is a water well. Unlike most firms, Studio Mumbai does not have a library of catalogs to refer back to. Instead, they prefer to create their own details. This forces them to consider the materials, craftsmanship, and context of each project more intently — as opposed to just taking standard details from a material manufacturer and fitting them in.

THREAD, an Artists’ Residency and Cultural Center in Sinthian, Senegal, designed pro-bono by Toshiko Mori, uses white bricks for walls and thatch and bamboo for roofs. The walls and roof undulate in sync, dropping low to create an entrance to one space before rising up to create cover for another. Rain water is allowed to run down these roofs into a network of underground canals, which in turn are connected to two reservoirs on each end of the center. As an incubator of Senegalese artistic talent, a performance space, and a cultural institution, THREAD keeps the village of Sinthian alive by collecting up to 40 percent of its water.

All three of these architects and their recent projects show us how old materials can still be employed by modern firms to create new forms of architecture. Old materials, assembled using old craftsmanship, can lead to some pretty ingenious designs.